Vidyasagar: A pioneer of women’s rights

Aminul || risingbd.com

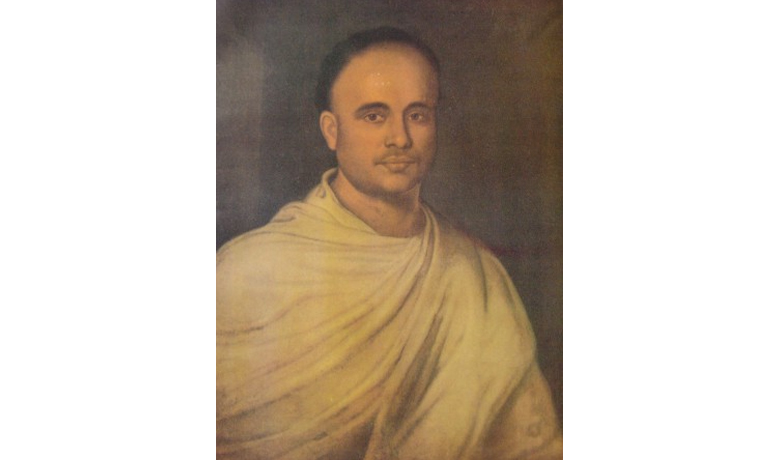

Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar

Aminul Islam: Young Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar stared at the magnificent building that housed Sanskrit College. He had been admitted to the college and there he was, with his father Thakurdas. The central part of the building was fenced off from its side portions by an enclosure. There were also walls surmounted by iron railings around the central part. Ishwar Chandra was puzzled.

“Why is this building fenced like this, father?” he asked.

“The central portion where the Sanskrit College is has upper caste boys studying in it. The other portion which houses the Hindu College, is where the others study. No Christian and Muslim boys are allowed in either college. The walls and enclosures are there to keep them out of the Sanskrit College.”

“But why should they be kept out?” asked the boy.

“So that they don’t mingle with each other. And now, let us go in and meet the teachers,” said his father, putting an end to the questions.

At just about nine, Ishwar Chandra was struck by the absurdity of the whole situation. ‘How can one human being be so superior to another, that even coming in contact can contaminate him?’ he wondered. It was just the beginning of a lifetime of such questions for him. Unlike many others, though, he didn’t merely stop at asking the questions. He set out to remedy the situation when he had the authority to do so, later on in life.

He soon got immersed in his studies. The course was vast. One had to first master the Sanskrit grammar before going on to study various other courses like, literature, rhetoric, Vedanta, smriti and nyaya or philosophy. It took a student 12 years to complete the entire course. Grammar was not easy. The rules were too complex and he had to sit up late nights to master them. It took him three years to finish the course of grammar.

In those days, when one completed the entire Sanskrit course except the philosophy course, one could earn the title of Judge Pandit and become an advisor of Hindu law to the District judge in civil courts. When Ishwar Chandra earned the title and also that of ‘Vidyasagar’, he got such a post, his father wouldn’t allow him to take it.

“You still have to complete the nyaya course,” he reminded his son. “Qualify yourself first before beginning to work.” And so Ishwar Chandra continued, and in 1841, when he was 21 years old, he completed his studies. He won over Rs.250 in cash awards and scholarships — a princely sum in those days!

He got a job of Sanskrit Pandit a few months later, in the Fort William College. In 1846, he returned to his alma mater, the Sanskrit College, as Assistant Secretary — a post equivalent to that of a vice-principal of today).

For Ishwar Chandra, this was an opportunity of a lifetime — to introduce some much-needed reforms in the educational system. He had not forgotten the arduous Sanskrit grammar, or the way the pundits came at their convenience, regardless of the college timings.

Among his recommendations was a rule that stated that attendance be made compulsory for both teachers and students. Punctuality was another one of the rules. He also recommended a change in text books and regrouping of the subjects. There were other suggestions too. He sent the document to the Secretary (Principal) Shri Russomay Dutta.

“Who is this upstart to impose rules on us — his teachers, who taught him barely five years ago?” fumed the teachers and expressed their displeasure. Needless to say, the Secretary rejected the recommendations. Vidyasagar resigned in protest, barely six months after joining.

“How are you going to survive without a job?” asked his friends.

“I would rather sell potatoes in the market to earn my living than serve an institution against my principles,” he replied.

However, he got the chance to serve Sanskrit College once again in 1850, as Professor of Literature and went on to became the Principal in 1851, when Shri. Dutta resigned. This time around, the Council of Education itself asked him to recommend changes to improve the working of the college. He submitted a ten-page report. It included removing the restrictions on admissions on the basis of caste and throwing open the college to everyone in addition to the previous recommendations.

“How can you even think of imparting sacred knowledge to the ‘Sudras’ (people of low caste)?” asked his old teachers aghast at his bold move.

“They are in no way inferior to the others. There have been so many non-Brahmin scholars in ancient times. Besides, if you are willing to teach Englishmen Sanskrit for the sake of money, why can’t you do the same for our own countrymen regardless of their caste?” he asked them quietly. “I am ready to resign, if you don’t want to support the recommendation.”

Fortunately for him, the Council accepted all the recommendations and soon the college was opened to everyone. One of the social injustices that had bothered Ishwar Chandra as a boy, had been rectified.

He then set about simplifying the teaching of Sanskrit grammar. He introduced a simple way of teaching beginners the fundamentals through Bengali grammar.

He also started a printing and publishing firm with a little investment. One of his lasting contributions to the printing industry was his simplification of Bengali typography and composition used in printing. He was associated with several Bengali and English newspapers and periodicals. He wrote about subjects like widow remarriage, educational reforms and against polygamy, in these papers.

He next turned his attention to the education of girls. Between 1857 and 1858, he started 35 schools with a total enrollment of 1300 girls. This was a path-breaking achievement in the conservative society of those days.

Another social evil that disturbed him deeply was the plight of child widows who were condemned to live like social outcastes. So he began to fight for their remarriage and rehabilitation. Being a realist, he also knew that unless such marriages got social sanction, they would not be successful. So he incessantly canvassed for public support through his writings. His vast knowledge of the scriptures helped him to argue his case, by quoting Sanskrit texts, which referred to them.

But he still had to face stiff opposition. When he actually conducted the marriages, many of his supporters and admirers were reluctant to be publicly associated with them. Vidyasagar ruthlessly severed connections with such hypocrites. He spent a lot of money in conducting these remarriages. He bought gifts and jewels for the bride and often had to borrow money from friends and well-wishers to pay for the expenses. Many unscrupulous young men took advantage of his goodness and came forward to marry the child widows. But once they got the gifts and jewellery, they abandoned the brides. Such incidents saddened Vidyasagar, but it only made him more determined to be more careful and continue fighting. He incurred huge debts due to his social work.

Apart from vilifying him for desecrating Hindu culture, his detractors also harmed him physically. Stones and dirt were thrown at him on the streets. Some actually planned to kill him.

Once he came to the house of a rich acquaintance who had been planning to kill him.

“I heard that you are planning to break my head with the help of hired thugs, so I wanted to save you the trouble. I am here and you can do whatever you want with my frail body right here in your own house!”

Needless to say, the said man hung his head in shame.

His publishing firm soon picked up enough profits for him to pay off his debts. His ceaseless campaigning for legal sanction against widow marriage finally bore fruit and in 1856, the Widow Remarriage Act was passed. He lived to see the movement spread to other states, notably Maharashtra and the southern states.

All through his life, he worked for the betterment of the society at large, with no thought for himself. “Vidyasagar had the genius and wisdom of an ancient sage, the energy of an Englishman and the heart of a Bengali mother,” wrote his friend and poet Michael Madhusudan Dutta, praising the great social reformer. Ramakrishna Paramahamsa called him a ‘great sanyasi’ who sacrificed his own interests for the sake of society.

Today, when the plight of the girl child and the condition of women in the society seems to be no better than it had been in the 19th century, we need someone of the same idealism and grit as Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar to bring about a radical change in the society – someone who doesn’t fall prey to populism or get marked by the corrosive effect of power and the attendant corruption.

I am sure such a person exists amongst us – in each one of us. All we need to do is awaken the person and fight for the right cause!

risinhbd/July 29, 2015/Aminul

risingbd.com